Common Mistakes in FPGA ML Accelerator Design (and How We Avoid Them)

FPGA-based ML acceleration looks straightforward on paper: implement convolution, add parallel MAC units, stream data, and achieve high TOPS/W. But once a design moves beyond small demos and begins running real models at real resolutions, the engineering challenges shift dramatically. The bottleneck is rarely compute alone. Instead, it becomes a systems problem involving external memory bandwidth, data movement patterns, operator scheduling, and integration with software.

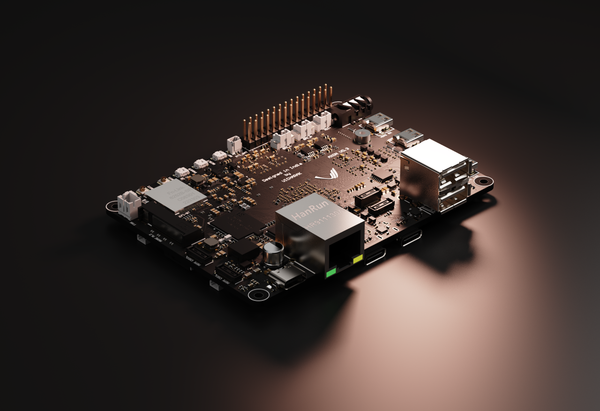

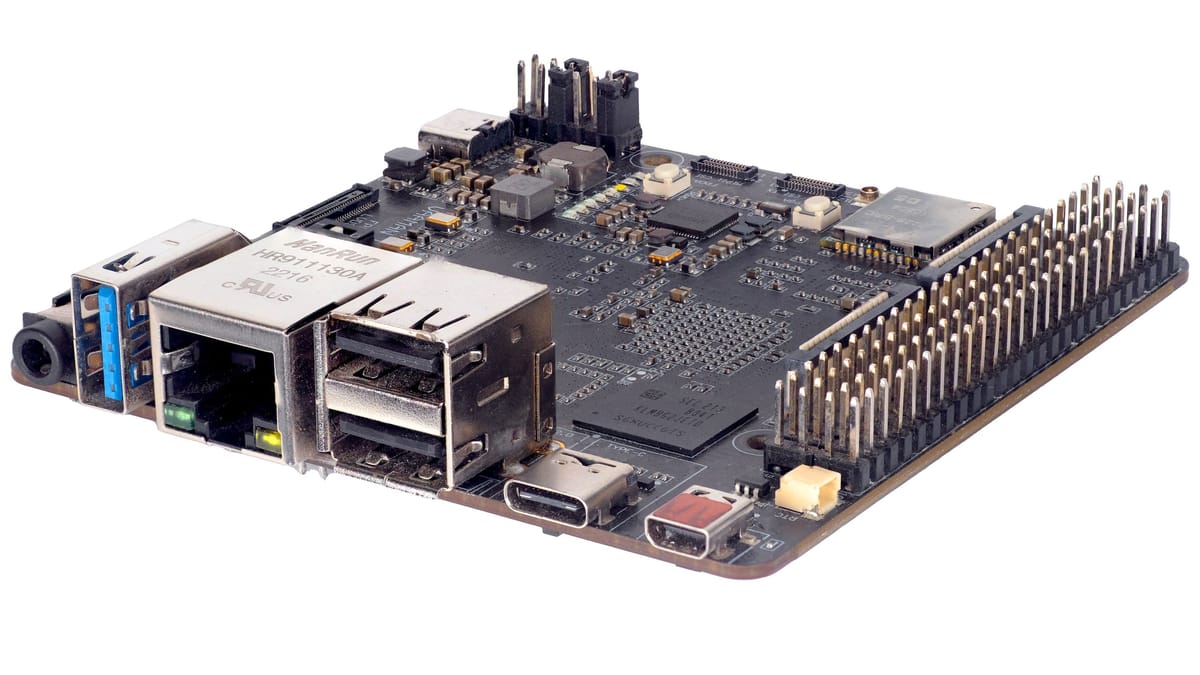

At Vicharak, we are building FPGA ML accelerators that must support multiple model architectures while operating within tight constraints on memory, power, and resource budgets. Over multiple iterations, we have found that the mistakes that slow projects down are not exotic; they are repeated patterns that show up in many first-generation accelerator designs.

This post describes common FPGA ML accelerator design mistakes we often see, and the engineering practices we use to avoid them.

Mistake 1: Designing for TOPS instead of real throughput

Many accelerator projects begin with a compute-first mindset. The design focuses on how many MAC units can be instantiated, what peak GOPS/TOPS can be reached, and how wide the datapath can be made. This gives impressive peak numbers, but it does not automatically translate into real performance on deployed models.

In practice, model execution speed depends on whether the compute stays busy. If the MAC array frequently stalls waiting for feature maps or weights, peak compute becomes irrelevant. The result is an accelerator that looks strong on paper but achieves only a small fraction of its theoretical throughput.

We avoid this by treating “utilization” as the key metric, not peak compute. Our architecture decisions start by studying dataflow, memory access patterns, and operator fusion opportunities, aiming to keep compute consistently fed rather than simply increasing the number of multipliers.

Mistake 2: Underestimating DRAM latency and access inefficiency

External DRAM is essential for modern models, especially at larger input resolutions like 640×640 and above. However, many designs implicitly assume DRAM behaves like a large, slightly slower SRAM. It does not. DRAM performance depends heavily on burst length, access locality, row hits, arbitration, and controller behavior.

A common early design mistake is issuing DRAM transactions in a way that creates fragmented, non-burst-friendly access patterns. This leads to high effective latency and low bandwidth utilization, even if the memory subsystem is theoretically capable of much more.

We treat DRAM as a constrained resource that must be scheduled carefully. Large transfers, burst-aligned layouts, and predictable access sequences matter far more than raw bus width. Architecturally, we design for locality and reuse first, and only then expand compute capability.

Mistake 3: Trying to store “everything on chip”

When DRAM becomes slow, a natural reaction is to increase buffering inside the FPGA. Teams begin to build large on-chip caches and store entire feature maps in BRAM, because it reduces immediate memory access pressure and makes the accelerator appear faster for small cases.

But this approach breaks quickly. On-chip memory is limited and expensive in routing resources. As model size or resolution increases, the design hits BRAM limits and becomes unscalable. The system also becomes hard to port between FPGAs because buffering assumptions are tightly coupled to the device.

We avoid this by designing for streaming and tiling early. Instead of attempting to fit large intermediate tensors inside the FPGA, we use structured tiling strategies that allow reuse without requiring full activation storage on-chip. This keeps the architecture scalable and portable.

Mistake 4: Building operator kernels without thinking about model-level scheduling

Implementing a fast convolution kernel is useful, but modern models are pipelines of many operators: convolution, activation, pooling, element-wise, transpose, reshape, quantization, and more. Many accelerators implement each operator as an isolated block but do not build an execution plan that reduces intermediate writes and redundant reads.

This results in a system that performs heavy DRAM traffic between every operator stage. The accelerator ends up spending more time moving intermediate activations than doing math. At higher resolutions, this becomes the dominant cost.

We approach the design from a model execution perspective rather than kernel-by-kernel optimization. The goal is to minimize unnecessary memory roundtrips. Operator fusion, streaming between stages, and careful tensor layout decisions often produce bigger speedups than improving a single operator’s compute.

Mistake 5: Tight coupling between software and hardware

Another frequent issue is designing the accelerator in a way that assumes fixed operator ordering, fixed tensor layouts, or fixed model structures. This might work for one model but fails immediately when the accelerator must run multiple CNNs or support ONNX models coming from different training pipelines.

When hardware is tightly coupled to one model, every change in preprocessing, padding style, layout, or post-processing requires RTL changes. This prevents long-term scale and productization.

We design hardware blocks to be reusable and parameter-driven, while keeping scheduling and configuration flexible. The goal is to support a family of models without requiring recompilation of RTL for every new architecture.

Mistake 6: Neglecting quantization and numeric behavior early

Many FPGA accelerators start with floating-point simulation and later attempt to move to INT8 or mixed precision. If quantization is treated as an afterthought, accuracy surprises become inevitable. Even worse, the required scaling and saturation behavior might not map cleanly to the datapath already designed.

Quantization is not only about using smaller bit widths. It affects how results accumulate, how intermediate values are clipped, how scaling is applied, and what rounding policy is used. These details determine whether the deployed model behaves like its software baseline.

We treat numeric behavior as a first-class design constraint. The accelerator’s arithmetic policies (rounding, saturation, accumulation widths) are designed explicitly and validated against reference implementations early, so that performance improvements do not come at the cost of unpredictable accuracy loss.

Mistake 7: Over complicating the datapath before the system stabilizes

FPGA engineers naturally want to optimize. It is tempting to introduce complex microarchitectures early: multi-level buffers, advanced schedulers, custom caching, and interconnect fabrics. But complexity is expensive because it increases integration risk and slows verification.

In early accelerator versions, speed comes more reliably from architectural correctness than from micro-optimizations. A clean datapath that is easy to reason about and verify often outperforms a complicated datapath that behaves unpredictably under stalls, backpressure, and arbitration.

We focus on clean pipelines and clear flow control first, and only add complexity when measurements prove it is necessary. Performance improvements must be justified with bottleneck data, not assumptions.

Mistake 8: Insufficient observability and profiling

ML accelerator performance is not obvious by inspection. If the design does not include performance counters and internal observability, teams have no reliable way to know whether stalls come from memory, scheduling, arbitration, or datapath under utilization.

The result is “optimization by guesswork”: adding compute, adjusting FIFO depth, rewriting kernels—without measurable feedback. This wastes time and can even make performance worse.

We build profiling into the accelerator. Cycle counts per layer, read/write bandwidth metrics, utilization indicators, stall reason counters, and per-operator timing are essential. These allow the team to optimize based on real bottlenecks instead of intuition.

Mistake 9: Treating ONNX or model import as only a software feature

Supporting ONNX import is a major advantage for usability, but many teams underestimate what it means for hardware design. ONNX models contain varied operators, layout conventions, and sometimes unexpected graph structures. If the hardware design assumes a narrow operator subset or fixed graph topology, it may technically “support ONNX” but fail on real-world networks.

We treat model import as a hardware-software co-design problem. Hardware operators are built with clear constraints, and the compiler/runtime maps ONNX graphs into supported hardware execution. In this approach, hardware remains stable and software evolves to improve coverage, scheduling, and fusion over time.

Closing thoughts

FPGA ML accelerator design is not only about implementing convolution efficiently. It is about sustaining throughput across full graphs, managing memory bandwidth under real workloads, maintaining flexibility across models, and building a system that can be measured, debugged, and improved continuously.

Most design mistakes happen when teams optimize the wrong thing too early: peak compute instead of utilization, buffering instead of dataflow, kernel performance instead of model-level scheduling. Avoiding these pitfalls allows an accelerator to scale from impressive demos to reliable deployments.

At Vicharak, this systems-first discipline is what enables us to build accelerators that are not only fast, but also reusable, adaptable, and production-ready.