Why We Built Shrike Lite: Breaking the Microcontroller Ceiling

At Vicharak, we spend a lot of time thinking about the layers of abstraction that engineers live in.

We all started with Arduino. You write digitalWrite(LED, HIGH), and the light turns on. It feels like magic. But it is "Software 1.0" magic. Under the hood, there is a CPU running frantically, fetching an instruction, decoding it, executing it, incrementing a program counter, and doing it all over again.

For many applications, this architecture is incredibly inefficient.

The CPU is a serial machine with a single thread of attention. It simulates parallelism by switching tasks rapidly (context switching). But if you zoom in, it is just one worker running around a warehouse. Eventually, driving a massive LED matrix or decoding high-speed protocols, they drop one. We call this "jitter."

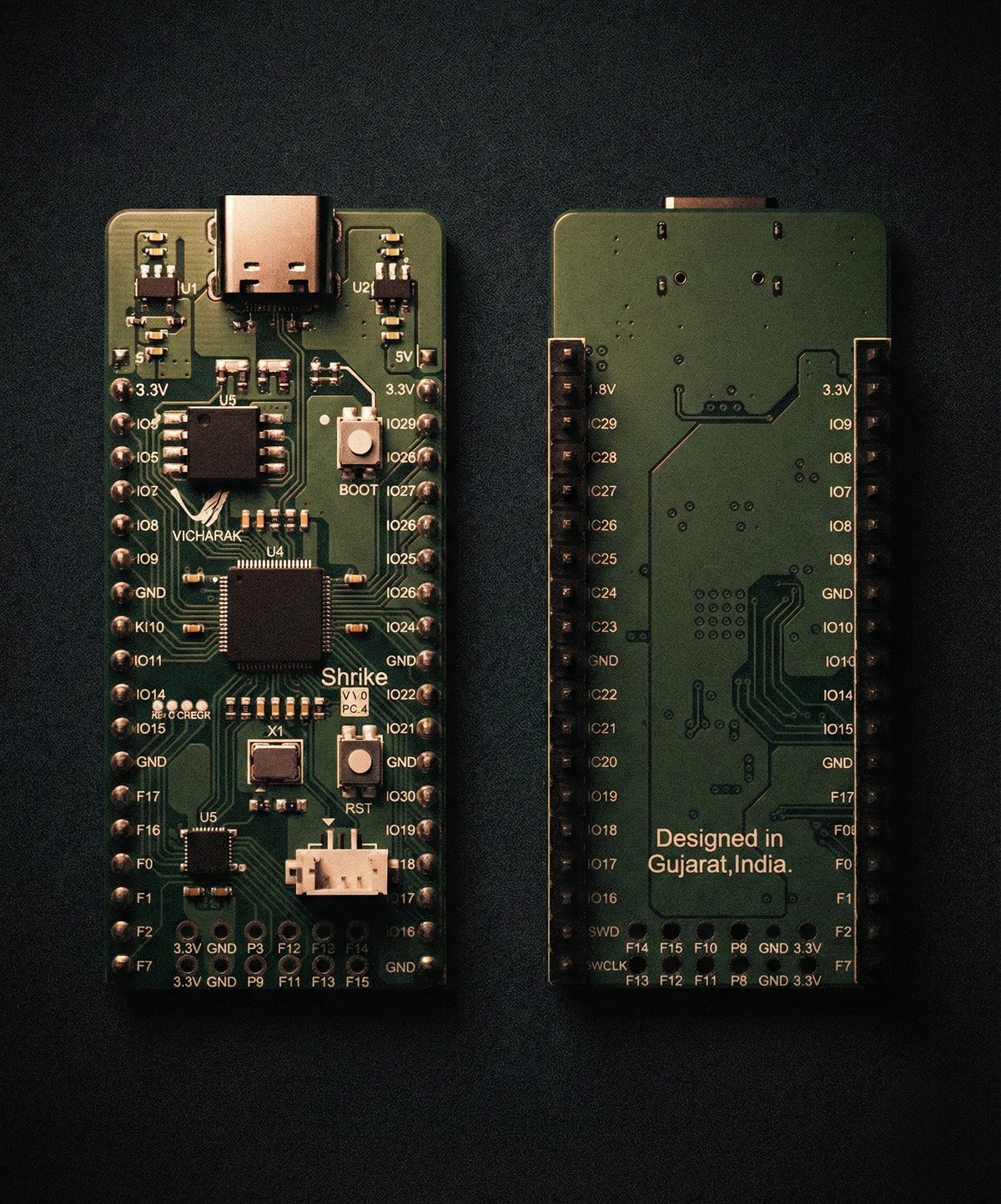

We built Shrike Lite to solve this specific problem.

It’s Just Gates. Literally.

We designed Shrike Lite as a hybrid system. It pairs the RP2040 microcontroller (familiar to anyone who has used a Pi Pico) with a Renesas ForgeFPGA.

For those who haven't worked with FPGAs, the mental model shift is profound, and it is something we want to bring to every maker's workbench.

On a microcontroller, you write code that tells the hardware what to do over time.

On an FPGA, you write code that tells the hardware what to be.

There is no instruction pointer. There is no fetch-decode-execute loop. There is no software. When you program the Shrike Lite's FPGA, you are describing the wiring of digital logic gates. You are arranging the atoms of the computer. It’s not a binary executable; you are creating a bitstream that configures the physical connections on the chip.

Once configured, the FPGA doesn't "run" code. The electricity simply flows through the gates you set up. It is instantaneous, deterministic, and parallel by default. It is the physics of the circuit.

The Bottleneck: Why We Moved Beyond Arduino

To understand why we created this board, you have to look at the pain points inherent in standard microcontroller architecture.

1. The Interrupt Tax

In the Arduino ecosystem, catching a fast signal requires an interrupt. The CPU must stop its current task, save its state, jump to the Interrupt Service Routine (ISR), execute the work, and jump back. This incurs a cycle penalty. If signals arrive too fast—say, from a high-resolution quadrature encoder on a robotics project—the CPU spends 100% of its time entering and exiting interrupts. The main loop freezes.

2. The Bit-Banging Trap

Communicating with non-standard protocols often requires "bit-banging"—manually toggling pins in a loop. This is CPU-intensive and fragile. If a background process (like USB communication) steals a few cycles, timing drifts, and the communication fails.

The Shrike Solution: A Dual-Brain Organism

We engineered the Shrike Lite architecture to mimic biology:

- Cortex (RP2040): High-level cognition. This handles C++ or Python, file management, USB communication, and user interaction.

- Cerebellum (FPGA): Low-level motor control and reflexes.

This allows you to offload hard, timing-critical tasks to the FPGA. The FPGA handles the chaotic, high-speed reality of the physical world, digests it, and presents clean, summarized data to the CPU.

Case Studies: Upgrading Famous Projects

Here is how Shrike Lite improves upon classic hardware projects where traditional microcontrollers hit a wall.

1. The POV Display / NeoPixel Wall

The Problem: Addressable LEDs (WS2812B) have a strict timing protocol (~800kHz). If the CPU is interrupted while writing data to the strip, the timing breaks, and the LEDs flicker. This makes it nearly impossible to drive LEDs while simultaneously reading sensors for Persistence of Vision (POV) displays.

The Shrike Way: You synthesize a custom "LED Driver" block in the FPGA. The RP2040 simply dumps a frame of color data into shared memory and returns to other tasks. The FPGA reads that buffer and generates perfect nanosecond-timing pulses for the LEDs. It never sleeps, and it never gets distracted.

2. High-Performance Robotics (FOC)

The Problem: Field Oriented Control (FOC) for brushless motors requires reading encoders and updating PWM thousands of times a second. On a standard MCU, the loop latency creates instability.

The Shrike Way: We move the encoder counting and PWM generation into the FPGA hardware. The FPGA counts pulses—even at millions of steps per second—without burdening the CPU. The RP2040 just reads the current "Position" value from the FPGA whenever it is ready. This provides hardware-level safety and zero overhead.

3. Logic Analyzers & Glitch Hacking

The Problem: Turning an Arduino into a logic analyzer is limited by how fast the CPU can toggle IO pins. You will miss fast glitches.

The Shrike Way: An FPGA is natively a parallel sampling machine. You can configure Shrike to sample 8 pins simultaneously at 100MHz+ and store the data in a FIFO buffer. We have effectively given you the tools to build a professional-grade logic analyzer for $4.

Our Mission: The Democratization of Silicon

You might think, "I don't need nanosecond timing right now."

But our goal with Shrike Lite is about more than just speed. It is about understanding the machine from the ground up. When you build a CHIP-8 emulator on an Arduino, you are simulating a computer. When you build a CHIP-8 on an FPGA, you are building the computer. You are designing the ALU, the program counter, the registers.

Critically, we priced Shrike Lite at ~$4 because we believe this capability shouldn't be a luxury.

Compute has become so abundant that we can now offer a dual-core 32-bit MCU and a custom logic fabric for the price of a coffee. In the industry, knowing how to design digital logic is a superpower. It is the difference between being a software engineer who relies on hardware, and a systems engineer who defines it.

Conclusion

We invite you to give it a shot. There is a learning curve—thinking in parallel is a challenge—but it allows you to step out of the single-threaded loop and into the fabric of the machine itself.

With Shrike Lite, you stop looking at datasheets hoping the chip supports the protocol you need, and you start writing the hardware to support it yourself.

It’s just you and the logic gates. And to us, that is beautiful.